- Start

- Team

- Projekte Luftkrieg

- Lancaster DV174 - Speyer

- 16.07.2016: Arbeitseinsatz Gedenkstein Speyer

- 01.10.2016: Gedenkfeier DV174 Speyer

- 09.12.2016: Nachfahre aus Großbritannien besucht Absturzstelle Speyer

- 25.01.2017: Militärische Ehre in Australien. Rückkehr eines besonderen Fundes!

- 24.03.2017: Nachfahren besuchen Absturzstelle DV174 Speyer

- 30.06.2017: Australische Luftwaffe überreicht Nachfahren Fundstücke

- 12.09.2017: Australische Luftwaffe überreicht Nachfahren persönliche Teile aus dem Speyerer Stadtwald

- 10.03.2019: Nachfahren aus Australien besuchen Absturzstelle DV174 Speyer

- 19.05.2019: Nachfahren aus Australien besuchen Absturzstelle DV174 Speyer

- Stirling EF129 - Limburgerhof

- Halifax DK165 - Haßloch-Speyerdorf

- Halifax JD322 - Waldsee

- Messerschmitt Bf 110, W.-Nr. 4805 - Haßloch

- Halifax NP711 - Leistadt

- Stirling EE872 - Ludwigshafen

- P47 Thunderbolt 42-26803 - Waldsee

- Douglas C-47 "Dakota" KG653 - Nackterhof

- Würzburg Radar/Scheinwerferstellung Waldsee

- B-17 "Flying Fortress" 43-37889 Mechtersheim

- B-17 "Flying Fortress" 43-37594 Speyerdorf/Mußbach

- Lancaster W4848 Ludwigshafen

- Lancaster DV225 Iggelheim

- B-24 Liberator 41-24147 Herxheim

- Halifax NA670 Bad-Dürkheim

- Halifax JD369 - Ramsen

- Lancaster HK603 WP-D, Mutterstadt/Limburgerhof

- Wellington R1789 Maxdorf

- Wellington Z1156 Ludwigshafen

- Wellington W5485 Mannheim-Neckarau

- Lancaster LL923 Biedesheim

- Lancaster DV174 - Speyer

- Lesefunde

- Projekte/Themen Allg.

- Introduction

- World War II Memorial Project

- World War II Memorial Jump Project

- World War II Memorial Walk Project

- Begehung und Dokumentation: Halifax Bomber „Friday the 13th“

- Filmprojekte Halifax NP711 Leistadt

- Ausstellung "Der Flugzeugabsturz beim Nackterhof 1944"

- Die Armkette von Soldat John E. Norton: Rückgabe eines Kleinods nach 78 Jahren

- Dauerausstellung "Der Halifax vom Haimerst", Waldsee

- Ausstellung "vorZeiten" - Archäologische Entdeckertour mit IG Heimatforschung RLP

- Gefährliches Erbe

- 100km/24 Std. Spendenmarsch IG Heimatforschung RLP

- Bastogne Historic Walk 2022

- Survey Universität Heidelberg, Vicus Eisenberg

- Bilderserie: Der 2. Weltkrieg in Rheinland-Pfalz - damals und heute

- Geoelektrik-Workshop

- Zusammenarbeit zwischen der IG Heimatforschung RLP und amerikanischen Wissenschaftlern

- Von Metalldetektoren, vom Sondengehen und wie es dazu kam

- Grabung GDKE Speyer 2018-2019

- Flugprospektion 2020

- Links

- Presse

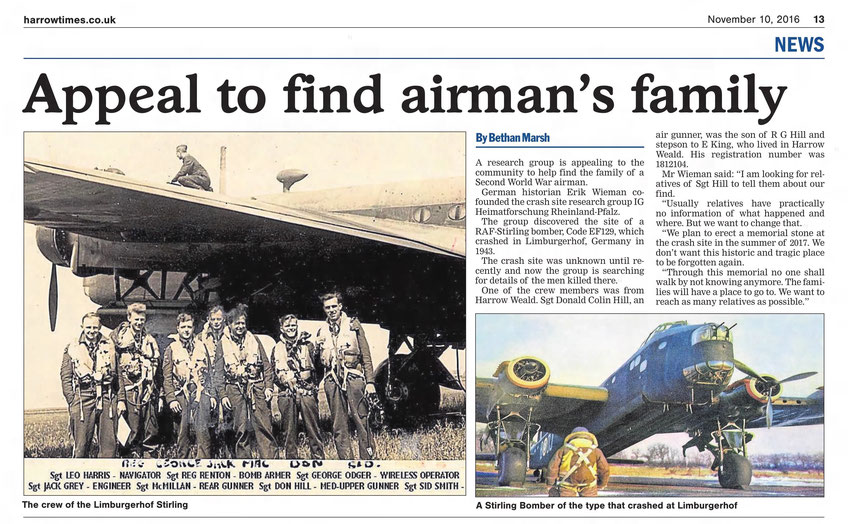

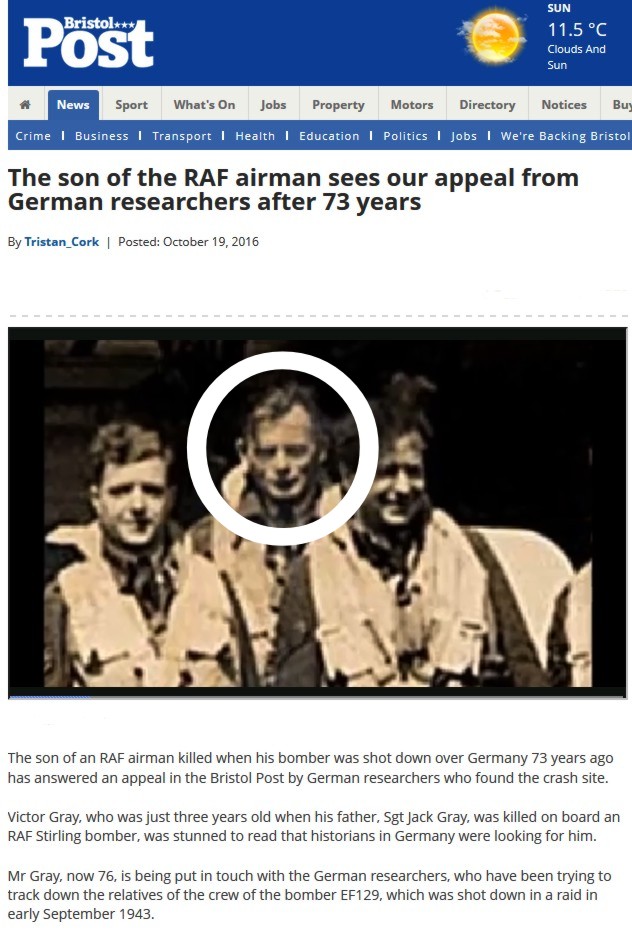

Crash site Limburgerhof - Stirling EF129

90 Squadron Royal Air Force

The crash site of EF129, a british WW2 Stirling Mk. III bomber, has been located. It crashed in 1943 at Limburgerhof-Kohlhof in Germany (Mannheim/Ludwigshafen-area). Over two thousand plane parts were found. On Remembrance Day 2016 a special find will be handed over to the family of the bomb aimer, Sgt. Reginald James Renton (UK), and the family of the navigator, F/Sgt. Leo Frederick Harris (NZ).

On Sunday, the 5th of september 1943 at 19:37pm a four engine english Stirling Mk. III bomber, Serial EF129 WP-Q left the airfield of Wratting Common in Great-Britain. EF129 was part of an armada of 605 four-engine bombers (299 Lancasters, 195 Halifaxes and 111 Stirling bombers). Their mission: a mayor night attack on the cities of Mannheim and Ludwigshafen. It was the biggest raid on these two cities in the Second World War. According to the police report of the Head of Police, commander Dewers, police commander of Ludwigshafen: "air raid from 23:21pm till 02.16am. 23:46: first activity of searchlights. Starlit sky. 23:49: Flak (anti aircraft guns) is firing all over the city. 24:00: bomber crews

are

marking their targets in the city center with so-called "Christbäume" ("christmas trees"/light markers). Subsequently mass drop of several kinds of bombs. The attack lasts for about 40 minutes". The police report further states, that about 62,000 incendiaries, 15,000 phosphorus bombs, 325 explosive bombs, 250 canister bombs, and

32 airmines (so called "Cookies") were dropped. In Ludwigshafen alone 50,000 people became homeless. 34 allied bombers were shot down by german night fighter planes and Flak. 11 german night fighters were shot down bei allied crews. It was a pure firestorm. Even three days later, warehouses were still on fire. In Ludwigshafen 127 people were

killed, 568 were wounded. Approximately 250 alied aviators from Britain, New Zealand, Canada and Australia were shot down. This was also the fate of the crew of Stirling Mk.

III, EF

129, 90 Squadron RAF. Most likely the bomber was attacked by a german ME110 night fighter

over Mannheim/Ludwigshafen. Ef129 crashed in the area of Kohlhof near Limburgerhof. According to a time witness

the burning aircraft came from the direction of Neuhofen / Waldsee. The aircraft

already flew at a very low altitude, and pulled up over Kohlhof. From the area of the BASF agricultural center to the south of Limburgerhof the Flak also

opened up at the bomber as it flew over the Kohlhof. The airplane flew a last (probably evading) left corner, then crashed into a ploughed field, with most of it´s crew. It was a mixed crew, a total of seven airmen, consisting of

five Englishmen, a Canadian, and a New Zealander. Nobody survived. The area was extensively

fenced off by the german military and police in the early morning of September 6, The wreck was still blazing. Ammunition exploded even two days after the crash. A few seconds before the burning plane crashed one of the crew members bailed out. The airplane was

flying directly over the house of a time witness at extremely low altitude.

The day after, the parachutist was found in the field, directly behind the house of the time witness. The time witness saw his parachute laying in the field. He must have died instantly.

Obviously his parachute could not unfold properly, the airplane was already flying way too low.

Other crew members were found at Kohlhof next to the broken off tail and

in the remains of the fuselage at the crash site.

Attack on Mannheim/Ludwigshafen 05/06 Sept. 1943 (released 1944)

Gradually, the bodys of the airmen were recovered and were temporarily buried at the cemetery of Limburgerhof, in the "Honor row of the Fallen", together with german war dead. After the war the crew was exhumed and buried at the allied cemetery of Rheinberg near Duisburg. To date the former graves in Limburgerhof cemetery are empty. No one was buried there anymore. After the exhumation in 1948 two of the helpers died because of the so-called "Leichengift/bodypoison" (like the elderly population used to call it). They probably were not protected well enough, infected themselves, and died.

Although it was known that the aircraft had crashed in the general area around Kohlhof, the exact location was practically unknown. The first thing we do is trying to find time witnesses. After searching for time witnesses in a local newspaper, we were astonished to find so many (5). They were visited by us, interviewed, and after that it quickly became clearer where the aircraft and parts of it had crashed. A wing fragment landed in a courtyard of a time witness at Kohlhofs main street.

The broken-off tail of the aircraft with the (twin-)machine gun turret crashed at

the edge of the Kohlhof into a field, next to the house of a time witness. The biggest part of the aircraft, the fuselage

with wings and engines and most of the crew, had crashed 700 meters further south into a field. Further away from Kohlhof than initially assumed, This field belonged to the father of a time witness. The time witness initially showed me an old floor map with the exact field, when I was a guest at his

home. The plots had changed somewhat after land replotting

after the war, but the exact location was clear. Together we drove to this

specific field and he showed me the exact spot where he had seen the crashed wreck when he was a little boy. Today's

landowner was quickly identified. He was also very cooperative.

The direct search on site could now

be initiated. One day later I put on my boots and went to the site.

A simple visual inspection without any technical aids, walking a few straight lines across the field, scanning the ground with my eyes, quickly brought the first evidence of the crash. Small

fragments of aircraft aluminum, some still had the distinct dark green / black camouflage paint of the outer hull of the aircraft and the

bright green paint of the inside of the aircraft, plexiglass fragments and (exploded) ammunition cartridges in caliber .303, of british origin, lying on

the surface. Time witnesses prove to be

the best initial way to find sites

like this. What I have found fittet perfectly compared to what they told me. Exactly here, the drama of 1943 must have taken place, and Ef129, or at least a big

part of it, must have come down in this field. Since the position was now known, further procedures

could be planned. The coordinates were recorded and

sent to the Archaeological Services (GDKE - General Directorate Cultural Heritage) in Speyer and I immediatly applied for an excavation permit.

In the meantime, current and older aerial photographs from the Second World War were evaluated and the area was photographed from the air with the help of my friend and member of IG

Heimatforschung, Ingo Stumpf, our pilot. The site was photographed extensively by me from several angles. This way even more definite conclusions could be drawn. From

the

air past/present ground penetrations, plane crashes as well, are often

visible due to soil discolorations or penetration characteristics like dark spots, differences in growth of a crop, etc. Also in this case. From the air the exact impact point of

the aircraft could be determined. Simultaneously the search for descendants of the bomber crew began. I started my search in New Zealand and Great Britain. Facts about the plane, the mission, a few details about the crew were already known beforehand. Except the picture of the New Zealand crew member we did not have any pictures of the rest of the crew. This should change soon. Through several links on the Internet I found out where they came from. And I found a name of one of the crew members on a homepage in the internet. Together with an image with the name and initials of the bomb aimer, Sgt. Renton. on a war monument. On this page, Sgt. Renton and other fallen soldiers from the 1st and 2nd World War were remembered on Remembrance Day (http://bishopmonktontoday.btck.co.uk/). Everything matched. Did he come from here?

From this village? I had to make

sure. Immediately I wrote an email to the webmaster of the site, Richard Field. He started a call on his website. Since everyone in this pitoresque village must know about eachother, the feedback did not last long.

And so it

happened: Around Christmas, December 2015, Valerie Renton, the daughter of the bomb aimer of EF129, Sgt. Reginald James Renton, killed in the crash at Limburgerhof-Kohlhof, was found. Together

with her daughter Sally-Ann.

Valerie Renton was very surprised to hear about us, about finding the crash site of her fahther after all these years and the circumstances of his death (something she had no knowledge of). An

"unexpected Christmas present" she said delighted. She

was a little girl when her father left for Germany on September 5, 1943, and never returned. She only knew he

had crashed somewhere over Germany. But where, more details, she had none. I gave her all the information about the crash I had and

sent her the first pictures of the crash site. It did not last long and the first

pictures from England arrived.

Our goals in this project are, in addition to the purpose of international understanding, to find

the crash site, to contact the descendants, if possible to find personal items of the crew we can hand over to the descendants so they can find closure, and after all research is done, to

ensure this historical site will not be forgotten again by placing a permanent memorial at the crash site, with the names of the fallen, their mission, etc. No one should simply pass this

spot not knowing. Without knowing what happened here and who died here. Passers-by can hardly imagine when they ask us what we are looking for. They usually are amazed when they hear about the

history. It did not last long till we got feedback from the achaeological services. My detecting permit was approved and I could start my research.

away from the computer, out in the field. With the initial

finds, our flight across the crash site in my mind, the area was encircled on a larger scale in order to determine how far I could find any debris or not. The circle quickly

became narrower. Not only plane parts surfaced. This area, this field was full of history! This is always fascinating. Nothing is visible, but they are there,

the silent witnesses of the past. After I got closer to the actual site of the crash, the spot where the first finds had already been made at the surface, the detector did not

cease to produce signals. The place was literally full of small aluminium aircraft parts, iron parts, exploded (british) .303 cal. cartridges. There were smaller and

bigger signals everywhere. A total of about 2000 parts were recovered. Also 280 exploded british cartridges, live ammunition, blown-off

projectiles. All in calibre .303 british. Most of the blown cartridges had no

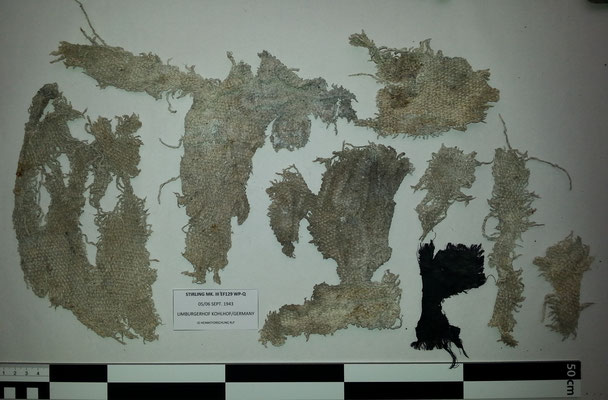

primers. When ammunition heats up in a fire, the inner heat usually blows out the primer in the back and the projectile in the front. A clear sign the aircraft was on fire, at least around the machine gun turrets. But I also found traces of the crews last battle. I found fragments of flak shells at the exact impact point of the fuselage. In addition, spent .303 cartridge shells were also found. Apparently fired at German night fighters during their last battle, in the evening of September 5, 1943. The burned-up remains of British incendiary bombs were also found, exactly where the plane had crashed. This leaves the question whether Ef129 dropped it´s complete bomb load or not. Or these incendiaries were from an earlier or later date. It can explain why the aircraft burned for two days and ammunition was still exploding days afterwards. Of course not all parts I found were harmless. Live ammunition and othet, still dangerous ammunition parts, were disposed of by the Bomb Disposal Unit of Worms/Rheinland-Pfalz. Apart from metal artefacts, also non-metallic

finds were discovered. Heavyly oxidized concentrations of finds contained several different materials and finds at the same time. Plastic parts, remains of equipment, etc. In a white aluminum oxidation layer, even cloth, burned wood, electronic parts etc. were clumped together. Aluminum dissolves into a white-bluish, powder-like substance in specific ground conditions. Obviously this had preserved other (organic) materials incl. wooden remnants. Due to sieving parts of the site, a bone fragment was also found at the main impact point of the aircraft. Whether this small bone fragment belongs to the crew or not is still open. Together with all the other finds it was handed over to the Archaeological Services of Speyer.

We

always hope to find personal belongings of the crew, or artefacts we can link to a specific person, especially

when descendants could be contacted. Be it a watch with a name, a ring

or any other personal items. Of course finds like this always have

a special significance to the descendants. We have found press buttons of

leather hoods, buckles, and metal parachute parts at the crash site. Personal items, but they could have belonged to any one of the crew. But items like this brings the crew much closer. In Sgt. Reginald James Rentons case however, we were even more lucky. No watch or ring was found, therefore another

part, which we can directly link to Sgt. Renton and his duty aboard Stirling EF129. Something only he could have operated or "triggered". Something with a direct link to Valeries father.

As a bomb aimer Sgt. Renton was

res-

ponsible for aiming and dropping the bombs up

front, in the nose of the plane. He determined when the bombs fell

by looking down, aiming through the bomb sight, and, at the same time, pressing the electrical release button. This button sent an electrical

signal to a combined electronic and mechanical release mechanism in the bomb bay, right next to the bombs, controlling the release of the bombs. We have found such a mechanism at the crash site. Two completely destroyed fragments and one which is hardly damaged. Even with the electrical wire still inside. After cleaning it will be handed over to Sgt. Rentons daughter and the family, if the

archaeological Services agree. Some parts might be of interest to the "Stirling

Aircraft

Project" in

England. Unlike Lancaster bombers from the WW2-era there are no Stirling bombers left. The goal of the "Stirling Project" in England is to reproduce

the Stirling bombers forward cockpit section. Because their are no detailed plans left for all components, their project is depending on Stirling finds, exact plans,

pictures, donations of collectors, etc. We would also like to support them here, in case we might find something they could need, or reproduce. Since two other Stirling

crash sites / projects of our group, near Ludwigshafen, are progressing, maybe we can contribute here in the near future too.

November 13, Remembrance Day, I will atend a special memorial service in the church of Bishop Monkton, the village where I initially found Sgt. Rentons name on the memorial, and will hand over this special aircraft part to the daughter and family of Sergeant Reginald Renton. 73 years after he died, a part of Sgt. Reginald Renton's plane and a part directly linked to him, will come home again.

We are pleased we could inform the descendants about what happened to their relatives

in the night of September 5/6, 1943. And where.

The almost forgotten site has been found and is secured.

As soon as our next goal, a memorial, has materialised, this will be a plave of remembrance for the

descendants, but also a place to reflect, for every other person passing by. Lest we forget.

Erik Wieman

Update:

Descendants of the folowing crew members could be contacted:

- Sgt. Reginald J. Renton (Great Britain, 2016)

- F/Sgt. Leo F. Harris (New Zealand, 2016)

-Sgt. George L. Odgers (Great Britain, 2016)

-Sgt. John E. Gray (Great Britain, 2016)

-W/O Sidney W. Smith (Great Britain, 2016)

-Sgt. Donald C. Hill (Great Britain, 2016)

-F/Sgt. Hugh Coles MacMillan (Canada, 2017)

All families of the crew could be contacted!

Courtesy of the Harris family, New Zealand

Visiting the Crew of Ef129, Rheinberg War Cemetery, Oktober 2016

Update january 2017:

Groups Remembrance Plaque reaches

the Harris family in New Zealand

Please follow this Link!

IG Heimatforschung and the crash of Stirling Ef129 Limburgerhof on CTV

Canadian Television (videoclips, pictures)

Browser: Internet Explorer